Oh, little book, from this my solitude!

I cast thee on the waters – go thy way…’

Don Juan's first edition, 1819

2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Byron’s epic poem Don Juan. Or rather it marks the publication of the first two Cantos of that remarkable work, which was to keep him occupied until his death at Missolonghi in 1824.

By then, George Gordon, Lord Byron, had shaken the dust of England from his feet and become a wanderer on the face of the earth. His marriage had failed and the rumorous scandal of his incestuous relationship with his half sister Augusta had made his native land too hot to hold him. Fetching up in Venice, he finally settled into the Palazzo Mocenigo early in 1818, with the menagerie of pets, servants and passing trade which was to turn it rapidly into a tourist attraction. ‘Strangers would bribe the servants for a view of its busy, vaulted vestibule, where two monkeys, a fox and a couple of mastiffs had made themselves a loud home.’ Here Shelley would visit him – a hopeful mediator between Byron and Shelley’s sister-in-law Claire Clairmont in the matter of their daughter Allegra.

Into this melodrama of a life stepped ‘Don Juan’, Byron’s new hero.

Ford Madox Brown's The Finding of Don Juan by Haidee

Not for him this time the dark romance of Childe Harold, the vaunting heroics of The Corsair or the histrionics of The Bride of Abydos. In Don Juan he gives us the epitome of the anti-romantic hero. The legendary Sevillian libertine, immortalised by Tirso de Molina, has been turned on his head and become a boy at the mercy of women in general, seen through the eyes of a cynical world-weary narrator, Byron himself – chatty, urbane and often very funny indeed.

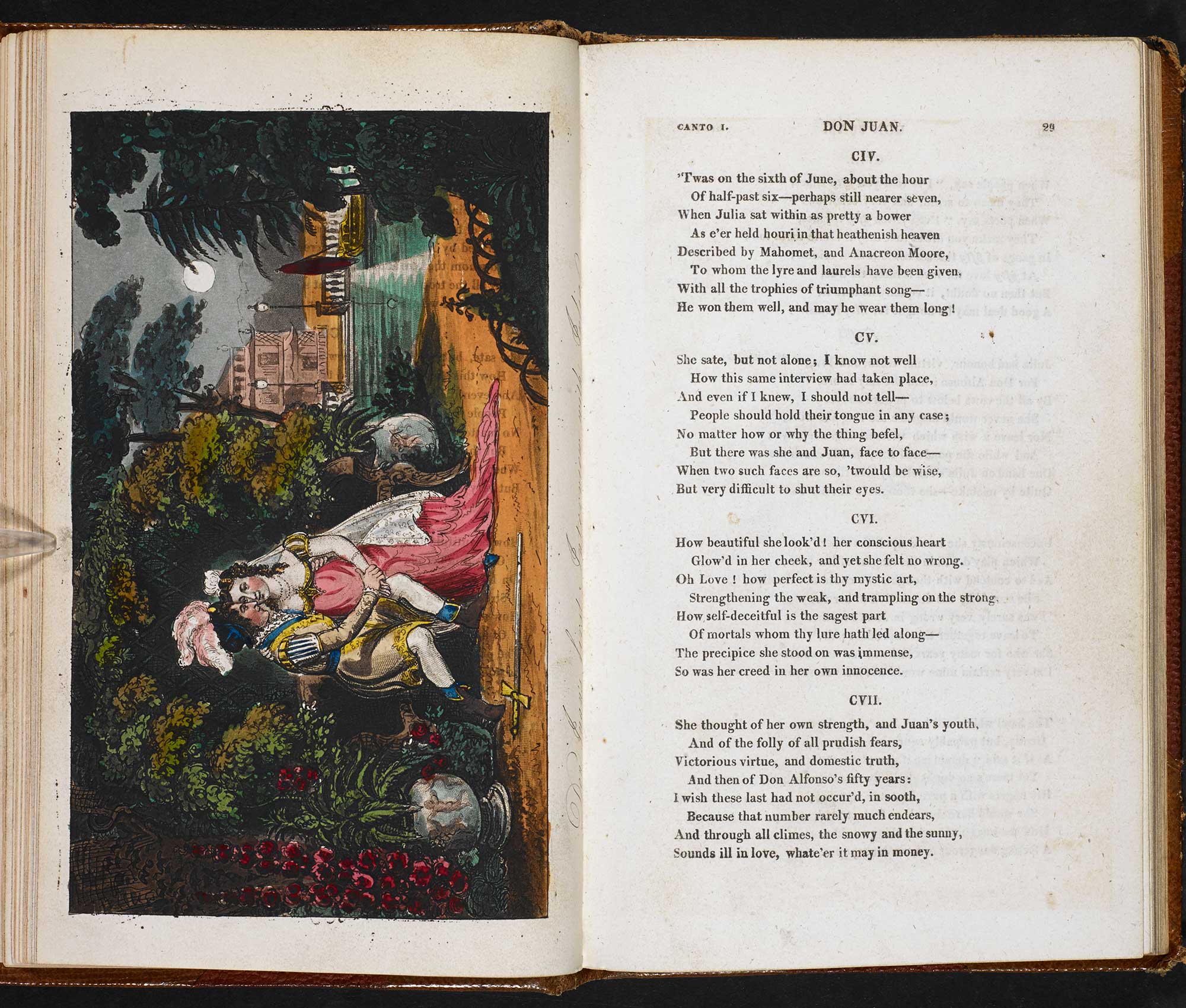

Don Juan is a mock epic, mockingly dedicated to Wordsworth, Coleridge and the Poet Laureate Southey. The first Canto tells of Don Juan’s seduction by the married older woman, Julia, at the age of 16, as a result of which he is sent away to sea. Canto 2 tells the story of a shipwreck in which Don Juan is the only survivor, cast ashore on a Greek island, where he awakes in the arms - inevitably it seems – of the second great love of his life, Haidée.

Eugene Delacroix's sketch for the Shipwreck of Don Juan. Courtesy of the V&A.

This bald summary does no justice to the scope of the poem itself, its extravagance, its joyful richness and its helter-skelter pace. Byron himself said he was aiming at a tone ‘lightly astringent, mildly scathing – like youth itself’, but being Byron, he takes great delight in throwing brickbats around with gay abandon. No one escapes – poets alive and dead are pilloried: Ovid is a rake, Anacreon’s morals don’t bear scrutiny, Wordsworth is crazed and Coleridge drunk. Southey’s verse reminds him of nursery rhymes, while the politician Castlereagh is dismissed as an ‘intellectual eunuch’. But the worst is reserved for Annabella Milbanke, his spurned wife, gleefully recreated as Don Juan’s mother: ‘Some women use their tongues – she look’d a lecture, each eye a sermon…’

The whole thing completely unnerved his publisher, John Murray, and most of his friends. Childe Harold had made his name and fame, so what was one to make of this exuberant and satirical stuff? His London friends, John Cam Hobhouse, Douglas Kinnaird, Scrope Davies and Tom Moore - all sufficiently worldly one would have supposed - were unanimous in advising that the work should not be printed. Harriet Wilson, Teresa Guiccioli (only recently installed as Byron’s mistress) and Caroline Lamb dismissed it as frivolous, immoral and not romantic. Byron was amazed and exasperated. In a letter to a mystified John Murray, Byron wrote: ‘ Do you suppose I could have any intention but to giggle and make giggle?’ Only Shelley loved it, recognising in it ‘something wholly new and relative to the age, and yet surpassingly beautiful’.

From Don Juan, Cantos I-V, illustrated by Isaac Cruikshank, published in 1826.

The first two episodes of what would turn into an epic of love and war were finally published in 1819, but alas without Byron’s rebarbative dedication. The publication of the next three Cantos was delayed by Murray until August 1821 – the publisher remaining unconvinced – while the rest of the poem was finally published at intervals by John Hunt. And yet this collective failure of nerve only serves to throw into relief the extraordinary genius of Don Juan and its creator. In it we experience what Isaac Asimov called ‘Byron’s utter lack of reverence for everything – even himself.’ In Don Juan, Byron had found the perfect vehicle for satirising not only the age in which he lived, but his own lordly excesses and romantic adventures, and he did it with wildly inspired invention, mockery, wit and – just to keep his romantic readers on their toes – unforgettable flashes of lyrical beauty.

We are all wanderers, and for better or for worse, slaves of the ‘fiery dust’ that flesh is formed of. For this year’s awards, poets and romantics are invited to turn a Byronic eye – and ear – on their own experience.

Sue Bradbury

Trustee of the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association